What the Industrial Revolution Taught Us About Our Desperation to Be Seen

From the Industrial Revolution to Bourdieu and Dana Thomas: Why cultural capital, not wealth, is the new marker of exclusivity.

What the Industrial Revolution Taught Us About Our Desperation to Be Seen

It is no secret that human beings have an innate desire to be seen. From trying to get your mother’s attention when she glances at your sibling to buying overpriced logo-covered clothing that screams purchasing power, we are all, in some way, trying to say:

I’m here!

But being here is not enough. To exist in a meaningful way, we must be here as someone. As Heidegger wisely puts it in Being and Time, “To live is to find oneself in the world.” This means that beyond mere survival, our fundamental pursuit is to shape an identity and have that identity recognized.

This struggle is not new. If we go back in history—specifically to the 19th century, during the Industrial Revolution—we see how the very structure of society shifted, forcing individuals to redefine what it meant to be someone in an increasingly vast and impersonal world.

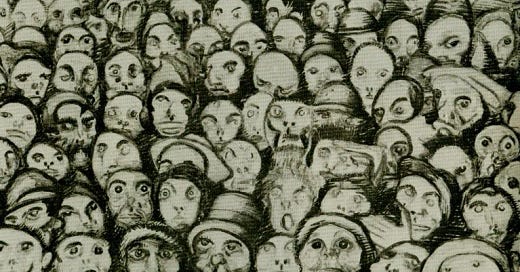

Before industrialization, life was largely confined to small communities where social roles were fixed and familiar. You were known—by name, by trade, by lineage. Identity was tethered to stability. But as cities expanded with the rise of industry, something changed: communities dissolved into crowds.

Suddenly, being known was no longer a given. Instead of belonging to a small village where your presence mattered, people found themselves among thousands, walking the same streets but remaining strangers.

In a big city, who are you?

At the same time, class structure was undergoing its own transformation. The old aristocracy—once the static holders of power—faced the unsettling reality that wealth, once a birthright, could now be earned. With industrialization came the rise of a new elite: the self-made bourgeoisie. Social mobility was no longer just a dream; it was a possibility. But with this shift came uncertainty. Class was no longer a fixed identity—it was flexible, performative, achievable.

This change bred a deep anxiety: if status could be gained, it could also be lost. And so, people sought new ways to assert who they were in this shifting social order.

It was in this moment that high fashion became more than just clothing—it became a statement. No longer was luxury simply about material wealth; it became a tool for recognition, a way to tell the world: I am not just anyone.

As Pierre Bourdieu later theorized, wealth alone is not enough to secure status—cultural capital plays an equally crucial role. Taste, refinement, and exclusivity became markers of distinction. The elite used craftsmanship, rare materials, and intricate designs not just for aesthetic pleasure but as social armor, ensuring they remained distinct from the rising working class.

But exclusivity has an expiration date. With mass production making luxury appear more accessible, fashion slowly lost its luster. No longer confined to the elite, high-end brands became aspirational rather than unattainable. Luxury was still desirable, but it was no longer rare.

This commercialization of fashion gave rise to something new: the era of branding. Logos, once discreet, became loud declarations of status. The logic was simple: in an anonymous crowd, visibility was everything. Mass media further amplified this, turning high fashion into a spectacle of aspiration. Dana Thomas, in Deluxe: How Luxury Lost Its Luster, details how true craftsmanship gave way to marketing, shifting luxury from what you own to what others perceive you to own.

But what happens when exclusivity itself becomes mainstream?

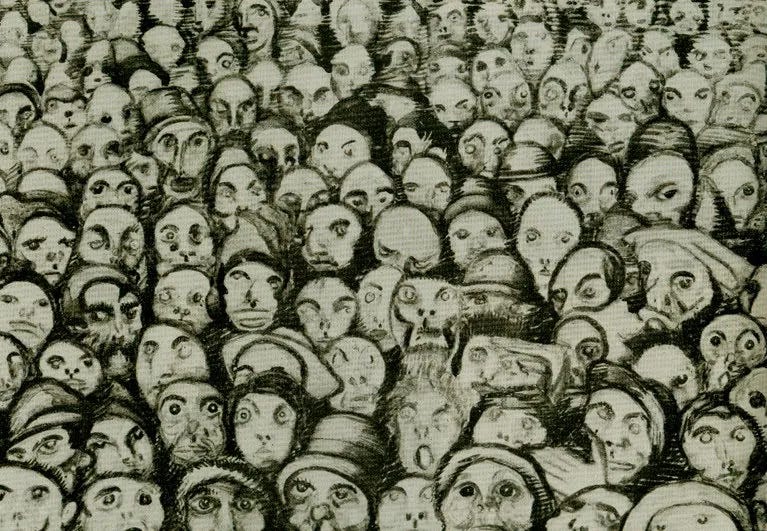

Fast forward to today, and the same struggle persists—but on a much larger scale. The industrial metropolis has been replaced by the globalized digital world. If the 19th century saw people trying to stand out in a growing city, today, they are trying to stand out in a world where billions of voices compete for attention.

In a globalized world, who are you?

In an era where fashion, wealth, and even experiences can be commodified and replicated, true status now lies in what cannot be purchased. The rise of social media has made it clear: logos alone no longer impress. After all, a fake designer bag can mimic the real thing, but what cannot be counterfeited is knowledge, intellectual depth, and cultural engagement.

This is why we are now witnessing a shift—what some might call a “post-high-fashion” movement. Luxury brands, recognizing that material exclusivity is no longer enough, are pivoting towards intellectual capital. The true elite today are those who possess something rare: curation, education, and deep cultural fluency.

Miu Miu’s Summer Readings Pop-Up, Alaïa’s Bookshop Café, and a resurgence of artist collaborations signal this transformation. Luxury today is no longer just about wearing something expensive—it’s about having the cultural literacy to engage with what is meaningful

The crowd is real. It is large. And no matter how much we try to deny it, we are small. But the only way to grow bigger is inside.

If industrialization forced people to redefine themselves in an anonymous city, and mass media turned visibility into a commodity, then today’s challenge is different: in a world where everything is purchasable, the only true marker of distinction is what cannot be bought.

👏🏽

Achei bem legal! Manda seus textos para MH e pro Ana da Enjoei. 😉